- Articles Index

- Monthly Features

- General History Articles

- Ancient Near East

- Classical Europe and Mediterranean

- East Asia

- Steppes & Central Asia

- South and SE Asia

- Medieval Europe

- Medieval Iran & Islamic Middle East

- African History (-1750)

- Pre-Columbian Americas

- Early Modern Era

- 19'th Century (1789-1914)

- 20'th Century

- 21'st Century

- Total Quiz Archive

- Access Account

The Anabaptist Commune of Münster 1534 -1535

By Komnenos

Category: Early Modern Era

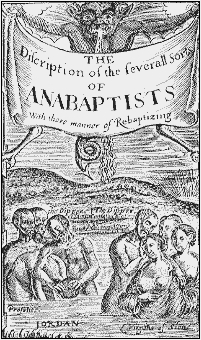

The fragmentation of Germany into a large number of medium and small feudal territories, that had hindered a coordinated organisation and communication between the splintered groups of armed peasants, had been one of the reasons for the easy defeat of the rebellion, but the division of Germany had revealed an even more perplexing phenomenon: a distinct North-South divide in the extent of the rebellions. Whilst the revolt had raged in the Southern and the Central regions of Germany, and its consequences had devastated whole areas for decades to come, the North and North-West however had remained virtually untouched by large scale rebellions. One can only speculate about the reasons: the peasants in the North might have been slightly better of than their Southern counterparts, or the relative thin settlement in the agricultural regions of the North had prevented larger and organised rebellions of its population. If the reformation and the subsequent rebellions hadn't reached the peasants to the same extent than in the South, it had however entered the cities and towns of the North. The Northern cities of Germany in the beginning of the 16th century could look back on a long and distinguished history, most of them had belonged to the Hanseatic League, the powerful merchant league that had dominated the trade in the Baltic Sea and most of Northern Europe from the late 13th century onwards. Coastal cities and important ports, like Lübeck, Hamburg, Bremen, belonged to the most populous and richest cities in the Holy Roman Empire, but the Hanseatic League also had a large number of cities in the interior of the HRE amongst its members, many of them in Westphalia, a fertile plain in the North-West of Germany. Dortmund, Breckerfeld, Soest were influential trading centres in the Westphalian region, but possibly the most important was Münster, a city of some 10.000 inhabitants in the heart of the Westphalian agricultural country, and the seat of the regional Archbishop, one of the most powerful ecclesiastical potentates in the HRE. At the beginning of the 16th, the Hanseatic League was already in decline, constant conflicts with the emerging Kingdoms of Denmark and Sweden had ended its trading monopoly in the Baltic, and the increasing economic difficulties of the leading Hanseatic cities had resulted in the equally increasing dissatisfaction of their population with the municipal authorities. In addition, the phenomenon of migration of impoverished peasants into the urban centres had increased the social pressures on the cities. Lübeck had witnessed plebeian revolt, under the leadership of Burgomaster Jurg Wollenweber in 1533, that for a while had threatened to overthrow the patrician regime that had ruled the Hanseatic city for centuries, but a war with Denmark had ended the rebellion. The revolt in Lübeck had diffused into other Northern cities, without great success, with one notable exception. II. The Reformation had finally reached the Westphalian city of Münster in 1531 with the arrival of the Lutheran priest Bernt Rothmann who began to preach the Protestant creed, right in the heart of the town of the regional bishopric. Münster was a city over which the rule was divided, in a careful political balance act between the Archbishop and the institutions of the population of a, at least in theory, self-governing city. At the beginning of the 16th century, the citizens of Münster were far from politically united. Recent economic developments, not dissimilar to those all over the urban metropoles of the HRE, had intensified the tensions between various factions in the city, the influence of the patricians, minor aristocrats and rich merchants, who had controlled Münster hereditary for the last few centuries, had been rivalled by that of the up-coming class of craftsmen and lesser traders whose importance for the economy had steadily grown. The craftsmen were additionally organised in powerful guilds that controlled membership, regulated the out-put and adjusted the pricing of produced goods. The changing power constellations in Münster were reflected in the changes over the control of the most important governing body of Münster's citizens, the city council, that had been dominated by the patricians but at the time of Rothmann's arrival in the town had fallen into the hands of the plebeian guilds. The conflicts between the social classes of Münster had so far been of economic nature, struggling for shares in the dwindling income of the town, but with the arrival of the Reformation, it became another dimension. Rothmann who had come to Münster as an ordinary Lutheran priest had undergone a process of radicalisation, result of a continuous persecution by the Archbishop and his followers amongst the city council. He had been prevented from preaching in the churches of the city and repeatedly the ecclesiastical had attempted to expel him from the town altogether. But he had also had strong support amongst the ordinary citizens who had protected him from any attempts to ban him from Münster, and on more of than one occasions from violent assaults. By 1532, Rothmann had become the spiritual and political leader of the rebellious faction of Münster's citizens, and as the priest in early 1533 publicly rejected infant baptism, and thus declared his adherence to Anabaptism, many of Münster's plebeian classes followed him on his step over to the most radical religious groups that the Reformation had spawned. “Anabaptism” that proclaimed the notion of a baptising of the adult believer, was not an entirely new phenomenon, exclusive to the Reformation of the 16th century. Early Christian groups had also rejected infant baptism, and some of the offshoots of the Hussite rebellion in Bohemia in the mid 15th century can be, with some right be regarded as the predecessors of the Anabaptists a hundred years later. The Anabaptist movement appeared in the immediate aftermath of Luther's Reformation, not so much as an organised and unified Protestant tendency, but as the result of independent and spontaneous radical interpretations of the Protestant beliefs by a whole series of preachers, operating independently in most regions of the HRE. The term “Anabaptism” in itself is mis-leading, far from demanding a second baptism, most Anabaptists did not recognise infant baptism at all and thus acknowledged adult baptism as the only valid rite to receive the believer in the community of the Church. Furthermore, the term “Anabaptists” as a generic term for all the various sects that appeared in the 16th century does not reflect the, sometimes, serious differences. Apart from the notion of adult baptism, the diverse “Anabaptist” sects had few common, but rather vaguely connected, ideological tenets. The return to the ascetic values of early Christianity, the believe in the immediate coming of “God's Kingdom on Earth” (“Millenarianism”) were some common traits, but the various groups differed greatly in details how to achieve the expected millenarian age, or which exact form it should and would take. That millenarian Anabaptism can be identified as the spiritual and political ideology of the social rebellions of the 16th century must not surprise, as the most radical critic of the ecclesiastical and governmental authorities, it offered the only coherent ideological context for the social and political demands of the oppressed peasants and the urban proletariat. In absence of any other ideology of liberation, the radical faith offered the most accessible and convenient justification for the demands and actions of the rebellious population. The defeat of the Peasants' Rebellion of 1525 had driven the surviving Anabaptist apostles underground, thus resulting in a further fragmentation of the movement. All over the HRE, Anabaptists priests preached secretly in clandestine meetings to the believers, often hunted from city to city by the authorities. The Empire had identified the Anabaptists as the most dangerous sect, and thus pursued its adherents with utmost zeal. The Imperial Diet of Speyer in 1529 had passed a law that had put Anabaptist teaching under severest punishment: [I]”...thereby declaring, that every Anabaptists and re-baptised person, men or women of mature age, should be transferred from natural life to death, and should be tried by fire, sword or similar means according to circumstances, without previous inquisition by ecclesiastical authorities.”[/I] The persecution of Anabaptists caused a large number of victims, exact figures are difficult to established, but it has been estimated that in Netherlands alone 50.000 Anabaptists were executed. That The Netherlands, then still under Habsburg's rule, witnessed such a large number of Anabaptist martyrs, had two reasons, firstly it was the domain of the reigning Emperor Charles V who was trying to set an example for the rest of his Empire, but also because here the Anabaptists had been especially successful. It had been largely the merit of one man. Melchior Hoffmann, born in Franconia, who, having converted to Protestantism and later to Anabaptism, had embarked in the mid 1520s on a Europe wide odyssey in order to preach the new faith. Being hunted from town to town, he had arrived in 1531 in Holland where he found a captive audience, and thus achieved a large number of conversions to the Anabaptist faith. The followers of his special branch of Anabaptism have become known as “Melchiorites”, a group that rejected the pacifism of other Anabaptist groups and advocated the violent over-throw of the existing society in anticipation of the imminent coming of God's Kingdom. The Dutch Melchiorites were subjected to brutal persecutions by the Imperial authorities, many of their followers were burned at the stake, and thus in the beginning of 1534, Jan Mathhijs the leader of the Anabaptist movement in Holland ( during Hoffmann's absence), a former baker from Haarlem near Amsterdam, decided to send one of his most prominent disciples, Jan Beukelszoon van Leiden to the only place that seemed to offer a safe haven for the persecuted believers: Münster in Westphalia. In February 1534 Jan Matthijs, accompanied by a large number of Dutch Anabaptist followed him. III. By the time, the two leaders of the Dutch Melchiorites, Jan Mathhijs and Jan (Beukelszoon) van Leiden arrived in Münster in early 1534, the city was already firmly under Anabaptist control. The year 1533 had seen a constant struggle for control between the two factions in the city, the party of the conservative Patricians, amongst them not a small number of Lutherans, and the Anabaptist party under the leadership of Rothmann, and the foremost exponent of the plebeian classes, Bernhard Knipperdolling, himself the son of a wealthy merchant who nevertheless had become a follower of the now openly Anabaptist Rothmann. At the end of 1533, the council was still in the hands of the “party of order”, a loose alliance of patricians, moderate protestants and allies of the Archbishop of Münster. It had made ineffectual several attempts to ban Anabaptists preaching in the city, to silence their leaders by exiling or arresting them, steady , but now slowly and surely the balance of power was shifting. Another prominent Anabaptists leader, Johann Schröder, had reached the city and begun to preach radical Anabaptist tenets, he was expelled for the fist time in December 1533, but returned and was again banned in January 1534, led out by council soldiers through a city gate, and brought back immediately by Anabaptist “Brethren” through another. The council looked on powerless. The city seemed lost. In such dilemma, the moderate city council turned to the only power that could offer some practical, namely military support: The Archbishop of Münster. It was to become a strange alliance, not only had the proud citizens of the proud Hanseatic city had been in a state of perpetual strife with the Archbishops over the rule of the city, but now the Protestant council sought the help of a Catholic power. It was not to be the last coalition that transcended religious boundaries in the wars over the reorganization of the HRE that followed the Reformation. Archbishop of Münster was a certain Franz von Waldeck, the scion of an old but minor dynasty from the wooded hills south of the Westphalian plains. He had been elected Archbishop in May 1532, after the sudden death of his predecessor Bishop Eric, who although having invested the proud sum of 40.000 Gulden in the purchase of the Bishopric, had only enjoyed his title for a year. That Bishoprics were sold to the highest bidder was no uncommon event in the Church, on the contrary. If Franz von Waldeck had to spend a fortune for the title, is not known, but he certainly wasn’t elected for his spiritual merits or strict adherence to the Catholic faith. It was an open secret that Franz had been living for decades in an illegitimate marriage which had produced eight children. His choice had been a political one: as the son of the Count of Waldeck, he had the domains of his family at his disposal, and thus military potentials, not be scorned. Franz von Waldeck's first attack on the practice of the Lutheran faith in his see in Münster had failed. In June 1532 he had demanded that the city would return to the Catholic rite, but the thread of violence had for once united both the radical and moderate Protestant factions, and in January 1533 the Archbishop had been forced to grant religious freedom in Münster. A year later, however, the situation had changed dramatically, not the moderate Lutheran dominated town and Churches anymore, but the radical Anabaptists. It was not only the result of the persuasiveness of the Anabaptists preachers, that might have convinced the citizens of Münster to the new faith, but also a simple exchange of population: while there had been a exodus of Catholics and conservative and wealthy Lutherans, they had been replaced to a constant influx of Anabaptists from all over the HRE, mostly from The Netherlands who had come to seek refuge in the city. The Dutch Melchiorites began to identify the city as the place that was most likely to promise the advent of the new Millennium, and as the vanguard of their soon following leaders, had flocked in their hundreds to Münster. In early February 1534, Archbishop Franz von Waldeck was no longer prepared to see his city become the European centre of the Anabaptist heresy, ignoring his earlier promise of religious tolerance, he issued an edict that forbade the preaching of the faith and asked for the immediate arrest of all (re-) baptised persons in Münster and surroundings, a rather late attempt to enforce the Imperial edict of 1529. The citizens of Münster ignored the demands of its Bishop. Franz von Waldeck in the meantime had assembled a considerable force near Münster, prepared to let deeds follow his words, if necessary. On the night to the 10th February, a few of his remaining followers inside the city, supported by the few remaining moderate Lutherans, opened two of the city gates, and a couple of thousands of the Bishop's troops poured into Münster. The Anabaptists were taken by surprise, Knipperdolling and a few of the other leaders were captured and imprisoned. A few hours later the radicals had regrouped, had armed themselves and fighting on the streets of Münster ensued. The mercenaries of the Bishop stood no chance against the Anabaptists who knew their city better than the spiritless motley crew that Franz of Waldeck had assembled. The Bishop's force was driven back and fled the city, together with their allied citizens, and the imprisoned Anabaptist leaders were freed. Over night the Anabaptists, with the Bishop's help, had now taken complete control of Münster, had they been until now the dominating political force, they all over sudden had become a military as well. A week later Jan Matthijs arrived. The Bishop retreated to the nearby town of Telgte ( more than a hundred year later to become next to Münster itself the place, where the end of the Thirty Years War was to be negotiated) and on February 28 1534 begun the siege of Münster. The very same day, new council elections were held in the city, and with the last serious political opposition expelled or having left voluntarily, the Anabaptists won all 36 seats in the city council, electing Knipperdolling and Gert Kippenbrock as Burgomasters.

IV.

The first meetings of the new city council demonstrated the new power constellations in Münster. Whilst Knipperdolling and Kippenbrock, both born in the city, were the political figure-heads, the real rulers of the town were the leaders of the Dutch Melchiorites, the “Prophet” Jan Matthijs and his disciple Jan van Leiden. Had only a couple of years earlier the hopes of the Melchiorite Anabaptists concentrated on the southern town of Strasbourg, the imprisonment of Melchior Hoffmann there had convinced his followers that Strasbourg was not the place where “God's Kingdom on Earth' would materialise. But with Münster now at their feet, it seemed to have become apparent that God had chosen the Westphalian town as the seat of the “New Jerusalem” from where the new Millennium would be heralded. But the “New Jerusalem” was a beleaguered town, surrounded by the forces of the Archbishop, in a constant state of war throughout its existence, and thus the measures to be taken to welcome the new age had to be subordinated to the necessities of defence. The first action was conceived to ensure that treason from the inside would not repeat itself. A few days after the council elections, Jan Matthijs addressed the citizens of Münster and demanded [I]“that they should expel from the city all who would not submit to baptism in the blood of Christ.”[/I]

A few hundred citizens left to join the Bishop and his troops, leaving behind all their possessions to the community, the first act of enforcing a material equality that would hallmark the Anabaptist rule in the city over the coming months. The part of the remaining adult population that so far had not been, were baptised in the Anabaptist rite in a three day mass baptism. With the last doubters removed, and every adult in Münster seemingly committed to the cause, the preparations for the expected onslaught by the Bishop's force could begin.

The walls were re-inforced, the town divided into districts under the commands of prominent Anabaptists, the confiscated property used to acquire weapons and messengers were sent out into the Empire to ask for assistance from fellow believers. Franz von Waldeck, from his headquarters in Telgte, bade his time, whilst his forces drew an ever closer ring around Münster, he hesitated to attack the city outright, relying on starving the town into submission. Jan Matthijs, now the undisputed ruler of Münster, seemed to have grown impatient. On Easter Day, 1534, he rode out of the city, accompanied by a few followers, and by encountering the Bishop's troops, a fight ensued and the Anabaptist “Prophet” was killed by the Landsknechte. His head was put on a spike and displayed before the city's walls. If the Bishop had hoped, Jan Matthijs' death would discourage the defenders, he could not have been more wrong. On the contrary, the martyrdom of their leader only strengthened the Anabaptists' resolve, it further rallied the population together and whilst before Matthijs' death the roles of the political and the spiritual leadership of Münster had been somewhat unclear, his successor was to unite both. The summer of 1534 witnessed a number of the usual skirmishes between a besieged town and its besiegers. The Anabaptists attempted a few sallies, destroying a number of a Bishop's cannons that had harassed the city, but the gravest danger for the city had been an internal revolt of about a hundred citizens, led by Heinrich Mollenhecke who had been in charge of the city's artillery. They succeeded to arrest both Knipperdolling and Jan van Leiden, but were soon overcome by the vast majority of faithful believers who freed the two leaders and captured the rebells. Mollenhecke and fifty of his fellow conspirators were tried and beheaded. The inconsequential episode, however, had raised the spirits of the Bishop. Sensing internal disunity, he finally launched a massive attack on Münster on August 31 1534. A force of 8000 Landsknechte tried to storm the walls, but were repelled, leaving about 3000 dead. Jan van Leiden, after Matthijs' death, the spiritual leader of the Anabaptists, had also masterminded the defense, and after its success the grateful citizens decided to lay all power into his hands. In September 1534, suggested by the preacher Dusentschuer, Jan van Leiden was proclaimed “King of Jerusalem”, in an attempt to put the Commune of Münster into biblical tradition, as a Kingdom in direct succession to that of David and Solomon.

The role of Jan van Leiden throughout the months that followed his elevation is highly controversial amongst historians, and demonstrates the difficulties of historiography. The primary accounts of the Anabaptist Commune in Münster were written a few years after its demise, and almost exclusively by sworn enemies of the faith. All contemporary sources vilify the Anabaptists, and especially their two most prominent leaders, Jan Matthijs and Jan van Leiden. Modern accounts, on the other hand, especially those of Socialist writers like Karl Kautsky, have attempted to glorify the Commune which was identified as the prequel to Communist societies. With the city virtually cut off from the rest of the world, news from within Münster reached the outside very sparingly, and if from the steady trickle of renegades that reached the Bishop's camp, where the the Catholics used any information to bolster their anti-Anabaptist propaganda. The apparent splendour in which the new King ruled, the community of goods inside the city, and last but not least, the polygamy that the Anabaptists had introduced, were the most popular accusations directed at the rebellious city.

And it was foremost the 'polygamy” that captured the imagination of the people of the HRE, and still does most popular accounts. Rumours about the apparent decline of sexual morals inside Münster spread, or were deliberately spread by its enemies, like wildfire, and especially the conduct of the King who apparently had acquired a whole harem of faithful wives. There is indeed no doubt that the Anabaptists instituted polygamy for which Kautsky and similar writers offer a simple explanation. By late summer 1534, Münster had about 9000 citizens, 2000 men and 7000 women, most of them left inside the city by their husbands and fathers who had flown. Kautsky argues, that the Anabaptists emphatically attempted to prevent moral disintegration and to protect the large number of single women from sexual assault by the male population, and specially the number of mercenaries inside the walls. By marrying them to respected Anabaptist men, the women's honours could be protected, and the vast majority of such “pro-forma” marriages were never to be consummated. Instead of being the scene of libertine orgies, Münster had set an example for sexual morality. The truth is difficult to establish, but in view of the strict moral codex that most Anabaptist groups practiced, Kautsky's explanation seems the more plausible.

More difficult to explain, is the splendour with which Jan van Leiden conducted his office as the “King of Jerusalem”, more so in the view of dire economical situation Münster found itself in during the siege. Clad in magnificent robes, in stark contrast to the uniform modest clothing that had been introduced for the rest of the citizens,and wearing all the paraphernalia of a “King”, inclusive crown and sceptre, Jan van Leiden made his public appearances into great spectacles. His apologists have argued that Jan van Leiden's extravagance was not of his personal choice, but a clever propaganda move: to demonstrate the earthly splendour of the coming “God's Kingdom”, the King had to set an example. It seems however true, that with the progressing dire situation of the city, the “King”'s role became increasingly dictatorial, and the Commune that by definition should have been egalitarian acquired a despotic rule. Much of the dictatorial measures, that the “King” and his officials applied, were again necessitated by the war, the sometimes brutal oppression of any opposition against the “King” was justified with the experience of previous treason inside the city. Much has been made of a “proto- communist character” of the Anabaptist Münster, but if it was the realisation of the Utopian tenets of Anabaptism or the demands of a city under siege, is open to debate.

Quite early into the Anabaptist reign in Münster, the new rulers of the city had done away with the usual records of private property when deeds and debt documents had been destroyed. Abandoned houses had been distributed to incomers, means of production were taken into communal property, and the mass feeding of the population was organised. And the more the economical blockade by the Bishop's troops affected the town, the more it became necessary to share the ever dwindling resources. Over the coming months the entire wealth of the remaining population was channelled into the community, to organise the defence and to feed the increasingly starving people. And food supply became the overriding problem of Münster, the surrounding countryside had been occupied and pillaged by the Bishop's forces, who by late 1534 had closed the siege and prevented any supplies reaching the city. Famine broke out in the city, causing a high number of casualties, especially amongst the children and elderly citizens of Münster. At the beginning of 1535, the situation had become desperate. It had become obvious that short of miracle and God's intervention, Münster could not hold out much longer.The town was on its own, bereft of any potential allies. Whilst in the previous summer there had been some hope that military relief would reach the city, no such prospect existed now.

The Dutch Melchiorites had tried to organise an army in May 1534, a few thousand men had attempted to assemble in Holland and reach Münster by boats, sailing up the Rhine into Westphalia. But the army had been broken up by Habsburgian troops and no help had ever reached Münster.

In their desperation, the Anabaptists of Münster, turned to the Landgrave Phillip of Hessen, one of leading Protestant princes of the HRE. He was asked to mediate between the two warring forces, but true to his conduct in the peasant War of 1525, Phillip not only refused any negotiations, but even sent troops of his own to the Bishop's assistance. For the princes of Germany, regardless of their confession, it had become all to clear that the Anabaptist rebellion, was shaking the foundations of the earthly authorities of the HRE. The Imperial Diet of Worms on April 4, 1535 offered its fullest moral and material support to the policy Archbishop Franz von Waldeck. The re-conquest of Münster became an Imperial concern.

V. With Imperial backing, and in view of the precarious situation in Münster, on May 1535, the Archbishop formally demanded the unconditional surrender of the city. The Anabaptists refused, but “King” Jan van Leiden who despite all his religious fervour was fully aware of the untenability of Münster's position, granted free exit to all citizens who wanted to leave in anticipation of the upcoming storming of the city. A few hundred left the city in early June 1535, to be slaughtered by the Bishop's troops as they arrived at their lines. Still the Bishop hesitated with the decisive attack on the city, but when rumours reached him that Jan van Leiden planned to implement a “scorched earth” policy in Münster, by burning down the city and committing mass suicide, the Bishop pounced. As his prize possession, Münster had no value to him as a burnt ruin. In mid June, a refugee from the city reached the Bishop's camp, Gresbeck, a carpenter who offered to betray the city, by leading the Bishop's force into Münster via the weak spots of the defense that by now was terribly overstretched. On the night of June 25, Gresbeck ( who was later to write an account of the Anabaptist commune) led the Landsknechte into Münster though an unguarded gate. They met with desperate resistance by the half-starved population and it took several hours of street-combat to gain control over the city. A rest of about 200 Anabaptists barricaded themselves in the town-square, and resisted the Bishop's Landknechte for hours. Only when Franz von Waldeck promised safe conduct for the Brethren, the Anabaptists surrendered, only to be massacred immediately. After that, the Bishop's troops went on the rampage, enjoying the usual spoils of pillaging and raping. In the evening the whole city was once again under the Bishop's control, the Anabaptist experiment had come to an end after 16 months.

Jan van Leiden and Knipperdolling were captured alive, together with other Anabaptist leaders, and as to be expected, the Bishop exerted terrible revenge. The two were put in chains and together with another Anabaptist leader, Bernt Knechting, paraded through the entire Westphalia, put on show on market squares and customarily tortured. On January 22, 1536, Jan van Leiden, the “King of Jerusalem”, Bernhard Knipperdolling and Bernt Knechting were executed in the town-square in Münster, in presence of the Archbishop and his allied princes. The dying bodies of the three Anabaptists were put into cages which were pulled up on the spire of the Lamberti Church in Münster, as an exemplary warning to all religious and political heretics. It worked, the Anabaptist rebellion was the last open revolt in the aftermath of the Lutheran Reformation. As the oppression of the revolt in 1525 had marked the end of the peasant's attempt for social and political reforms in the agricultural regions of Germany, the end of the Commune of Münster in 1535 marked the end of urban revolts and of militant Anabaptism. For two or more centuries to come the economical and social situation of the German peasantry would not improve dramatically, while the urban plebeians would hardly participate in the increasing wealth and political importance of the cities. Radical Protestantism as the ideology of social unrest would disappear, Anabaptism survived until today in isolated and small communities (Mennonites, etc), but would never again try to realise its millenarian program with violent means. The Anabaptist commune of Münster was a desperate attempt to establish an egalitarian society based on religious doctrines, doomed from the outset in the face of overwhelming opposition, and can only be judged with view of the perpetual state of war it found itself in. Just like the Commune of Paris in 1871, it grew of war, and its politics were dictated by the necessities of war. Bibliography;

Emil Rosenow, Wider die Pfaffenherrschaft, Berlin, 1903

Karl Kautsky, Communism in Central Europe in the Time of the Reformation, London, 1897 Friederich Engels, Der Deutsche Bauernkrieg, 1850, from: Karl Marx-Friedrich Engels Werke, Bd. 7, Berlin 1960

Owen Chadwick, The Reformation, London 1964

Geoffrey Barraclough, The Christian World, A Social and Cultural History, London 1981 Belfort Bax, The Peasant War, London 1899

|